By Natasha Clarke – Research Associate, UCL

Imagine you went up to a bar, ordered a large glass of wine and it was served to you in a pint glass. People would look at you funny. The wine might not taste the same. You might not enjoy the drinking experience. We associate wine glasses with drinking wine, whisky glasses with whisky, pint glasses with beer… You get the gist. Often when we go to a pub and ask for a beer, they have a unique glass to serve each brand in. Different shapes and sizes of glasses are associated with specific drinks and many of us may perceive this as adding to the drinking session. Often, branding is displayed on glassware too, in case you’re so drunk during that fifth Guinness you need a reminder of what you’re drinking.

The point here is, from a marketing perspective, the glass is an integral tool which has been described as “integral to the moment of consumption”, suggested to have equal importance to other marketing methods (e.g. product design, sponsorship, packaging). Alcohol research indicates different sizes and shapes impact on drinking rates, yet glasses are not subject to the same scrutiny and control from a public health, harm-reduction perspective as other marketing techniques.

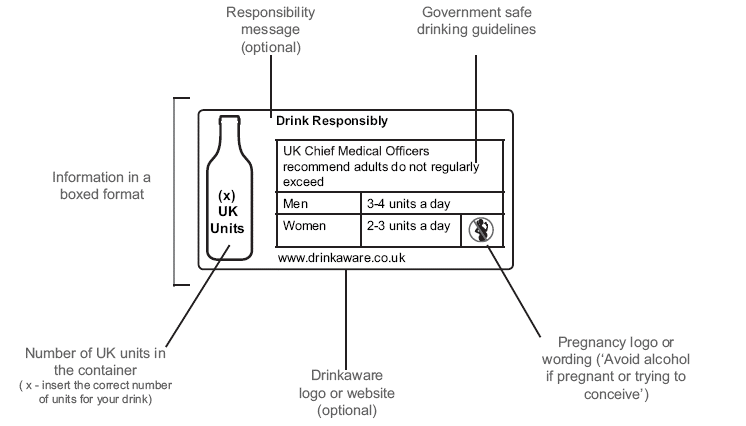

Currently in the UK, alcohol labels with unit guidelines are displayed (if you look hard enough) on alcohol products. A recent study suggested people pay minimal attention to these labels, and that is if they have the chance to be seen. What if you arrive at a house party and your friend pours you a vodka and lemonade? Or you are in a pub and you’re served a pint of draught beer? In addition, if labels in their current form are displayed and noticed they are unlikely to impact on our behaviour; many people lack knowledge of units, with knowledge lowest in those who drink heavily. Even in those who are aware of the concept of a unit, units are often not used to reduce drinking.

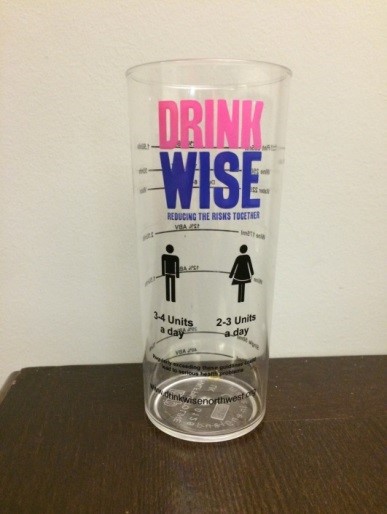

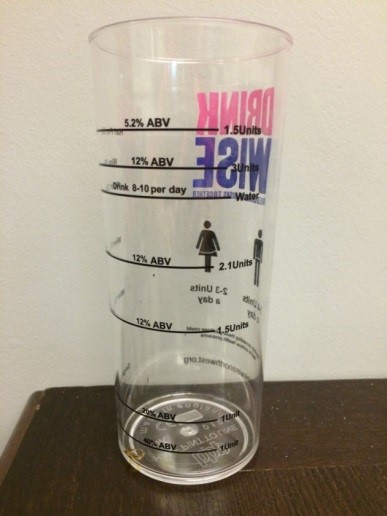

For a section of my PhD studies* I decided to investigate the impact of labelled glasses on drinking behaviour, in a population of majority undergraduate students. For my first glass label study I used a pre-existing measurement tool available from the drink charity Drink Wise to see whether glass labels with unit and warning labels, and safe daily guidelines** could reduce consumption compared to a plain glass of the same size and shape. I investigated this in a bar-laboratory with pairs of student social drinkers, to create an environment as close to a ‘typical’ drinking setting as possible. Results indicated the glasses did not influence drinking behaviour, consumption of beer and wine was roughly the same in each group over a 20 minute period.

I conducted focus groups to explore the potential reasons for the lack of differences between groups. The majority of participants stated that they could not relate to, and often did not use units to guide behaviour. Units were described as ‘not being taken too seriously’ anymore, with an emphasis on the message being boring and repetitive. This shows that even when unit labels are displayed and noticed at the moment of consumption, they are unlikely to be utilised to change behaviour, supporting previous research.

Another point raised in these focus groups (by female participants especially) was that calorie information would be more likely to change behaviour than unit information. Calorie information is mandatory on food, but is not required on alcohol products, which doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Appetite research indicates that the provision of calorie information alone has inconsistent effects on eating behaviour, but including exercise information (i.e. you will have to walk for 1 hour to burn off this pint) can be effective in reducing consumption and impacting food choice. In addition, websites/phone apps with drinking reduction tools, often include food equivalent information on their unit calculators (i.e. the calories in this pint equate to half a burger), a form of information that may be particularly useful for individuals who are more sedentary. Therefore, for my next study I investigated glass labels displaying calorie information with the addition of exercise or food equivalent information.

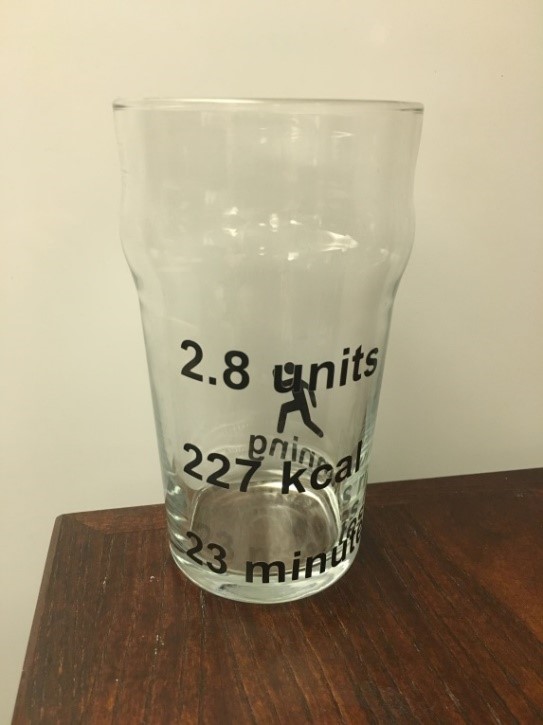

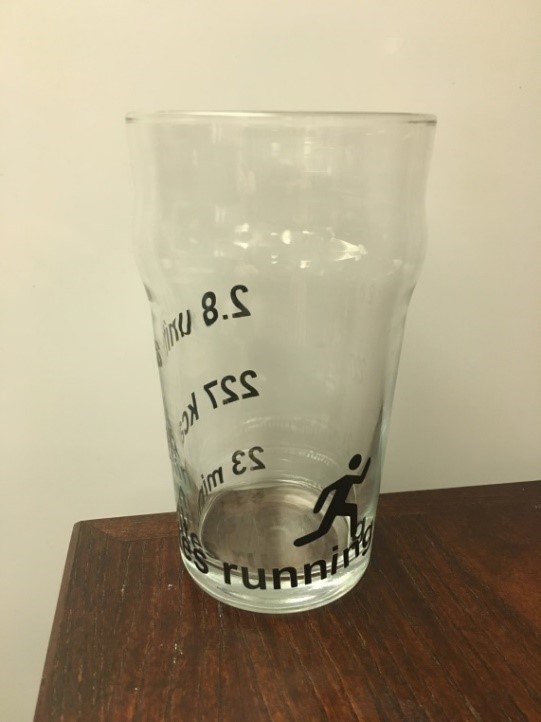

Another point raised in the focus groups was that the glasses were not aesthetically pleasing, and participants emphasised that they would not drink wine out of half pint glasses with ‘childlike’ labels. So for this study I used pint glasses and designed my own labels that were more simplistic (but large enough to be noticed). I investigated these glasses in the bar-lab, but this time I tested participants individually, as I found a very high modelling effect when testing in pairs, supporting research showing the same.

I found that for participants overall, these glass labels did not reduce drinking. However, when I explored this further and separated groups by gender, exercise labels significantly reduced drinking in female participants. This indicates calorie and unit labels alone do not reduce consumption, supporting recent findings by Maynard and colleagues in Bristol, in which displaying this information on a slip of paper also did not influence consumption. However, exercise equivalent labels show promise and this is an area that should definitely be investigated further, along with alternative forms of displaying nutritional information.

Again, I conducted focus groups to gain further insights into these findings. Participants were a lot more accepting of these labelled glasses (compared to the unit glasses used in the previous study) and the majority indicated that they could be effective in reducing drinking. Specifically they emphasised that they found it much easier to relate to and understand information when presented in this form. However, they did make it clear that this may change once in a drinking occasion and that I was ruining their fun. Fair enough. Many students do drink for sociability reasons, or for enhancement, and the majority do mature out of this. It may be that different populations are looking to change and are ready for their fun to be ruined. These types of labels may have increased impact in those who want to cut down, and therefore this form of information warrants further research in a variety of populations.

Another worrying finding from the focus groups was the potential of this type of information in increasing ‘drunkorexia’ behaviours, which I have previously written a blog about (see here). ‘Drunkorexia’ is a non-medical term used to describe diet related behaviours that are related to and used to compensate for the consumption of alcohol and its calories, such as skipping meals and excessively exercising. This does not necessarily mean nutritional information should not be provided as we have a right to know it, but measures to decrease the likelihood of these behaviours should be provided alongside.

To conclude, key findings from these studies were that:

1) Unit information alone is not sufficient for behaviour change. Nutritional information (alongside relatable equivalents) could be useful; participants were accepting of it and there is no reason for it not to be displayed. However, it is not a standalone intervention, and should be provided alongside other harm-reduction methods.

2) Glasses are an accepted and potentially effective method to display this information.

3) Focus group findings suggest that the drinking culture of students and their predetermined intoxication levels are very robust to change.

*Studies currently being written up for publication- contact author for further information.

**Note: previous guidelines (of 2-3 units per day for women and 3-4 units per day for men) as these studies were conducted before new guidelines were introduced.